Accessing an AWS hosted backend via IPv6

Reaching my API via IPv6 is not something I considered a high priority, but due to my prior experience with AWS I took the ability for granted. Recently I found out that it’s not as simple as I thought, since new AWS accounts do not get access to EC2-Classic, and to my surprise EC2-VPC has only recently started supporting IPv6, and only in us-east-1 with several limitations.

While not as trivial as I thought, there are simple solutions available, so I will describe the how and why of a couple of ways which we recently used at Takumi.

Background

This summer Apple announced that they would require all apps submitted to the App Store to support IPv6. At Takumi we were not concerned, as in the past I had noticed Amazon ELB’s have both AAAA records and a nice “dualstack” DNS name which had both A records and AAAA records for the underlying hosts – and the Takumi API is accessed through an AWS ELB. Besides our app not hardcoding any reliance on IPv4 (such as addresses or low level packet construction), we felt no pressure to reassess our connectivity.

Then about a month ago we got our first app rejection because our API was not reachable in an IPv6-only network Apple have setup for testing. To my surprise and despair there were no AAAA records, or a “dualstack” DNS name on any of our ELBs. Also I was surprised because our DNS setup did not include any AAAA records, it seemed Apple was testing this without using a DNS64/NAT64 network.

Quickly I found out that the reason for no AAAA records is that the Virtual Private Cloud offering of AWS does not support IPv6 (some support has been rolled out now in select regions), and I surmise that any resources created to wrap publicly accessible VPC instances are thus IPv4-only as well. All of our ELB’s and ALB’s have only A records, and no AAAA records associated with their DNS names. So the only way for an IPv6 device to access them is via (local) DNS64/NAT64.

To sum up: because we are a new customer of AWS, we are forced to use the VPC offering, which replaces EC2-Classic (as it’s now known), and this newer compute cloud does not support IPv6, which there is growing pressure around the internet to fully support. I was not pleased, and we are not the first app developer to get frustrated by this. And of course this shouldn’t happen unless your app has some unusual reliance on IPv4.

I however try and avoid getting submissions approved by explaining to the app reviewer that they should test things differently, and to be fair: if someone attempts to access our app via an IPv6-only network it wouldn’t work. So regardless of Apple’s testing procedures or fairness, getting this connectivity issue fixed seemed like the quickest and best solution.

First solution

A quick solution was to find a cloud provider which could provide a publicly accessible (IPv4 and IPv6) machine, and Digital Ocean became the provider of choice. I setup a debian machine there, an nginx proxy listening on the IPv6 interface which proxied to IPv4 backends using our ELB CNAME.

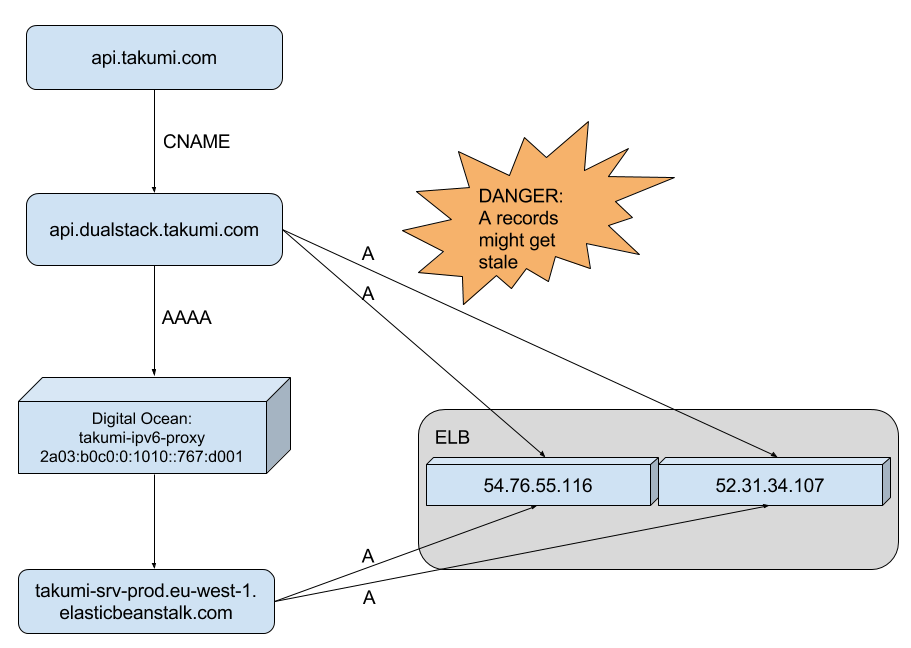

Workaround using Digital Ocean proxy node

Do those A records smell a little funky?

This simple solution only took an hour or so to setup, and got our app approved without any lengthy dialogue with Apple. The nginx configuration is very simple, as it’s simply functioning as a TCP proxy:

Caveats

While a quick and easy solution for most engineers to implement, this solution is both complex as it requires more moving parts and introduces a single point of failure in another datacenter with another provider – although the proxy is only used for IPv6. More alarmingly though, because it is not possible to create multiple DNS records with the same name with both CNAME and A/AAAA record types, I had to hardcode the ELB IP addresses as A-records on api.takumi.com, while the AAAA record pointed to the IPv6 address of the proxy.

This meant that if AWS changes the IP addresses of our ELB, which they might do at any moment and actively discourage any reliance on them, instead providing their own DNS names which should be accessed via CNAME entries from customer hostnames; our users would be stuck accessing outdated IP addresses which might not even answer, and certainly wouldn’t route traffic to our actual cloud servers.

A real solution would be to get a single DNS hostname from Amazon which would contain both IPv6 and IPv4 (AAAA and A records) which will reliably reach our load balancers, without the need to monitor for IP address changes, or add new proxy machines to our operational environment!

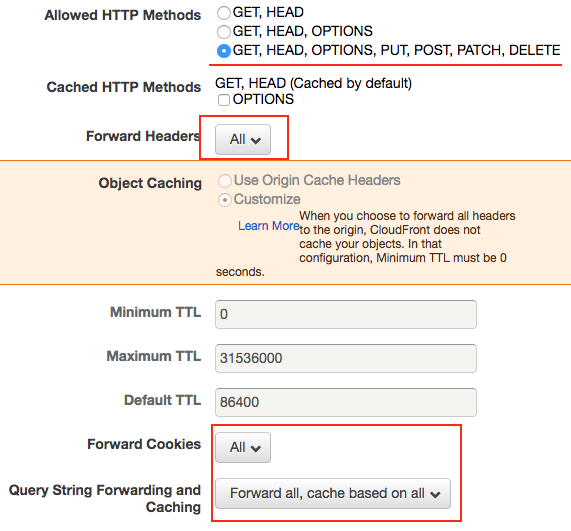

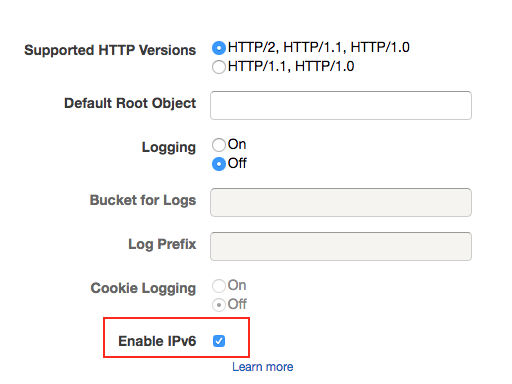

CloudFront to the Rescue

After consulting with a friend who’s an engineer with Amazon the simplest solution (with the added benefit of giving us lower latencies and DDoS protection) would be to setup a non-caching CloudFront distribution, the origin of which would be our production Elastic Load Balancer. When creating a CloudFront distribution it is possible to enable IPv6, and by allowing all HTTP methods, and choosing to forward all HTTP headers, and to forward all cookies and query string parameters, you’ve created a non-caching IPv6 accessible CloudFront distribution.

CloudFront Default Cache Behavior Settings

Relevant sections highlighted in red

CloudFront Distribution Settings

Relevant sections highlighted in red

Migrating

Since the new setup means having a CDN in front of our API, which essentially means deploying a distributed caching system in front of an API which almost by definition can be dangerous to cache accidentally, and we also rely on our own custom HTTP headers for identifying different client platforms and versions.

In short: we don’t want to switch all of our traffic onto CloudFront in one go as some insidious bugs might surface, and due to the aggressive caching and TTL ignoring of many large ISPs and DNS providers, the fallout could be rather painful.

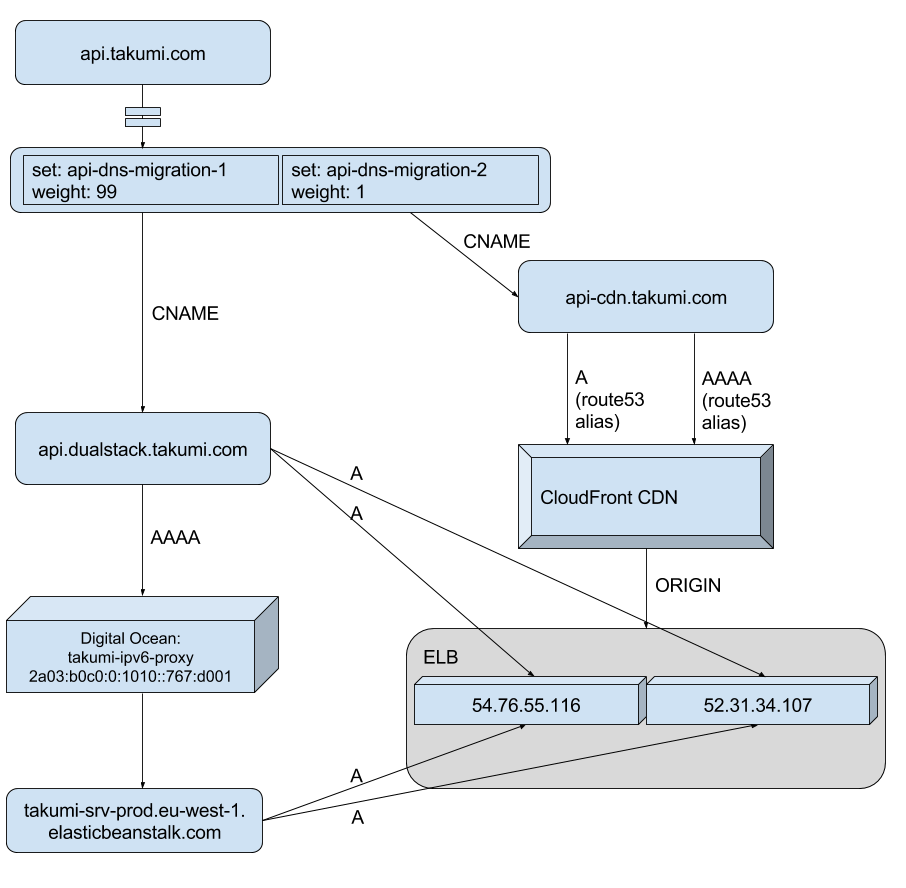

To migrate gradually to our new CloudFront distribution I then decided to change our main API DNS entry to a set of weighted records, starting with 99% of lookups receiving my workaround solution, and 1% the new CloudFront distribution.

Migrating to the new setup

Weighted DNS records allow a gradual switch

In a few days, if we have no issues with the new setup we can change the weights on those records to gradually move more traffic over to CloudFront, or all at once.

Final Setup

On top of getting the IPv6 support we need to avoid any random rejections at Apple, we’ll also benefit from better latencies and we are in a stronger position to deal with any DDoS attacks. Although this is an annoying problem due to inconsistent testing at Apple, and the fact that our cloud provider has not fully embraced IPv6, I am very pleased with this solution, and hope it can be of help to others.

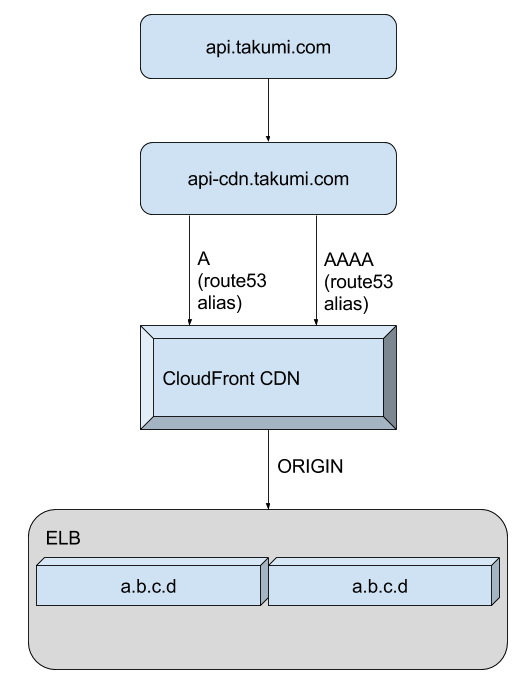

Final Setup with CloudFront

Simple and resilient

Note that in the last diagram actual IP’s have been replaced with a.b.c.d, as we

no longer depend on knowledge about those specifics further up in the stack.

This is an example of the same principles of building clean abstractions most developers know from writing software, but applied to systems design where they are of course equally important.

The chain leading up to the ELB should not need to know or care about the actual machines/IP’s comprising the load balancer. The fragility and complexity of the first solution can be mostly attributed to that leaky abstraction, which we have now gotten rid of completely.

Conclusions

IPv6 is coming, and I (we?) can no longer avoid dealing with it and learning more about it. Albeit random and potentially unfair this occurrence did trigger that, and in the end our API is more robust and flexible than before.

I hope our experience can help other app developers on AWS backends, although the CloudFront solution could be used by anyone with a HTTP/HTTPS accessible API.